The range of geospatial data in common use across the heritage sector is wide but can be grouped into five main categories:

- Base (Background) Mapping

- Primary Historic Environment Data (Survey)

- Secondary Historic Environment Data (Records)

- Non Historic Environment Survey Data

- Public Engagement and Dissemination

Read on to find out more about each category, then answer the Thinking About Data questions to consolidate your learning.

Base (Background) Mapping

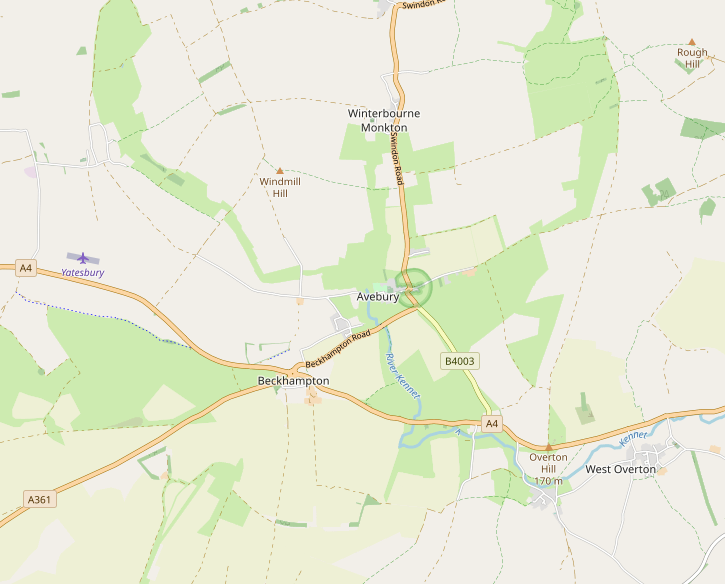

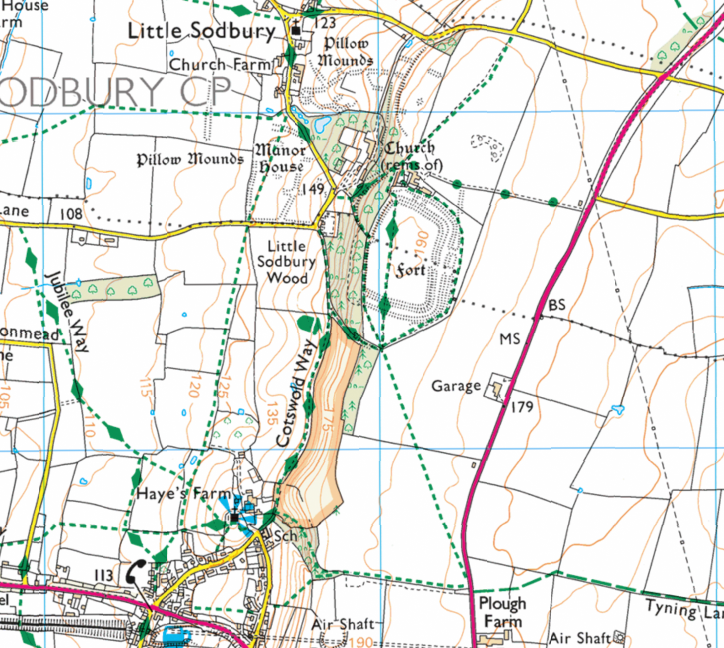

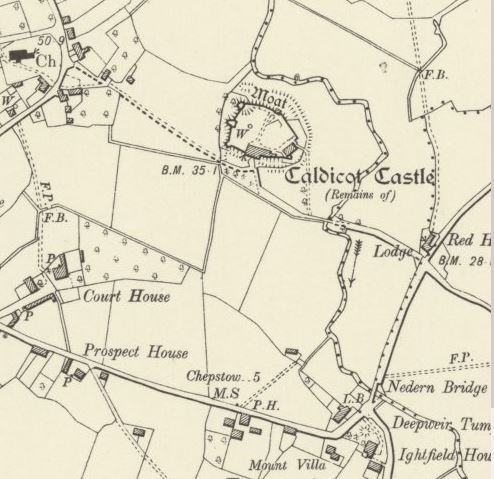

The first type of geospatial data to consider (and the one with which we are perhaps most familiar) is the base or background mapping. These take the form of medium to large scale map, over which all other date are layered and referenced.

In the UK the highest quality modern and historic mapping is provided by Ordnance Survey and their open data or licenced products are often our first choice for base maps, however there are many other useful datasets that can be integrated as basemaps in our GIS e.g.

- Open Street Map

- Google / Bing Maps

- Google / Bing Satellite Imagery

- Topographic Maps

- Historic Maps

Primary Historic Environment Data (Survey)

Geospatial data are routinely collected as part of a range of archaeological survey techniques including:

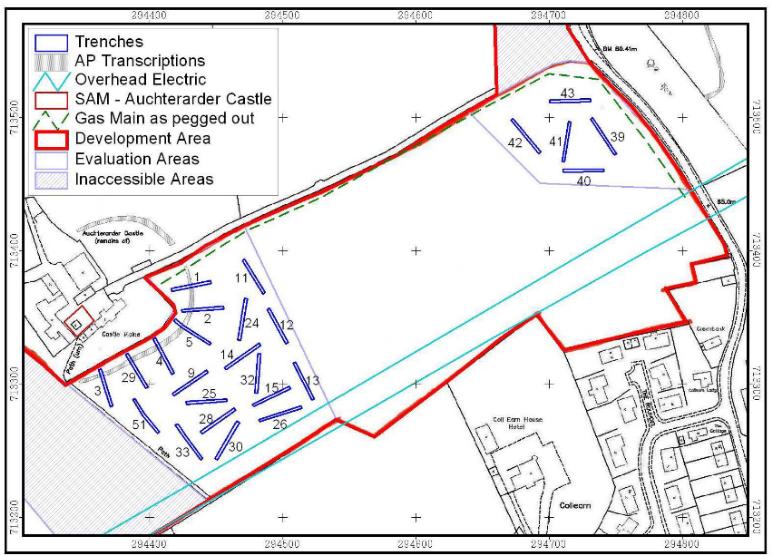

- Excavation

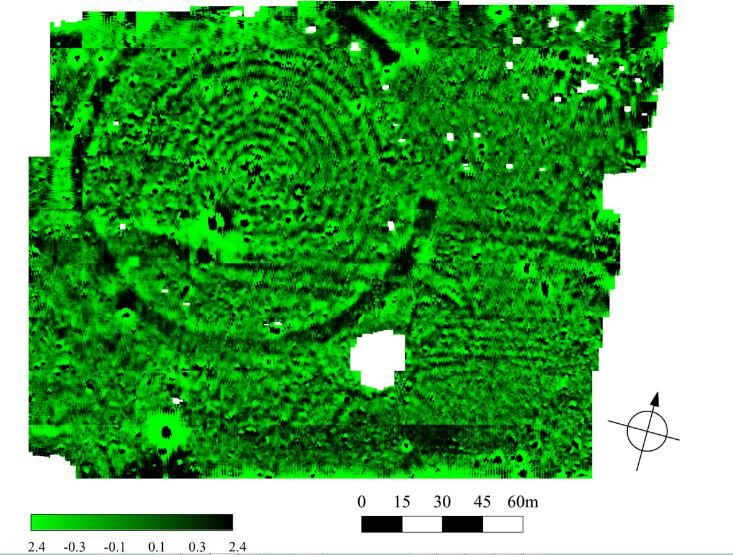

- Geophysical survey

- Topographical survey

- Aerial reconnaissance

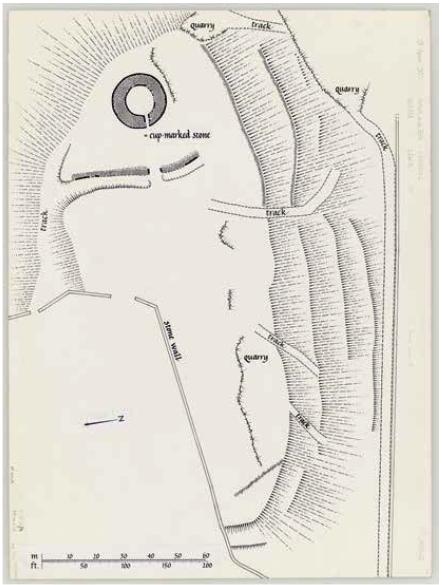

- Walkover survey

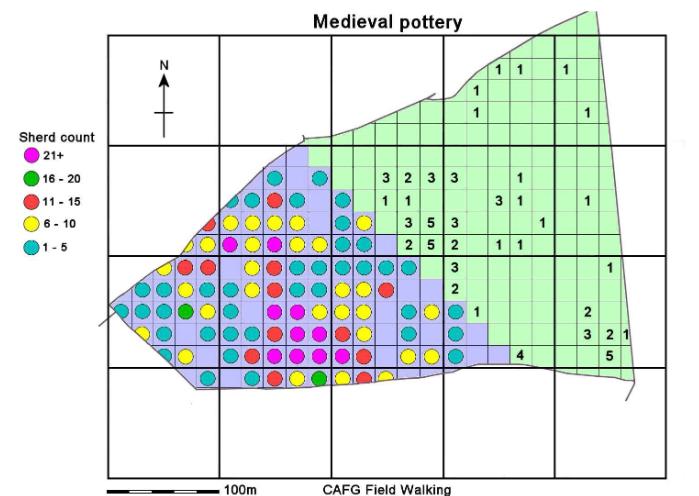

- Fieldwalking / artefact scatter survey

These data may be in “born digital” i.e. collected in georeferenced formats that are easily imported into our GIS, or they may require transformation and georeferencing. GIS is critical to the management of field survey data, ensuring high-quality, interchangeable and integrated data. We will learn about how to integrate a range of primary sources in this course.

Location data can also be derived from other survey data, which are not always collected with the historic environment in mind but nevertheless have huge implications for archaeological reconnaissance and resource management. Examples of these types of data include:

Craig Hill © RCAHMS

Fieldwalking results Wimpole Estate

© Cambridge Archaeology Field Group

Geophysical survey, Stanton Drew Stone Circles

© Bath and Counties Archaeological Society

Layout of Evaluation trenches, Castlemains Auchterarder

© Rathmell Archaeology Ltd

Secondary Historic Environment Data (Records)

The primary records are often collated into geospatial databases, allowing cross examination of different data from a range of sources.

The most widely known example of geospatial databases in the UK are the Historic Environment Records. These exist to collate and signpost users to information relating to “landscapes, buildings , monuments, sites, places, areas and archaeological finds spanning more than 700,000 years of human endeavour.” You can follow this link to Historic England’s description of the history of HERs and their role for more information.

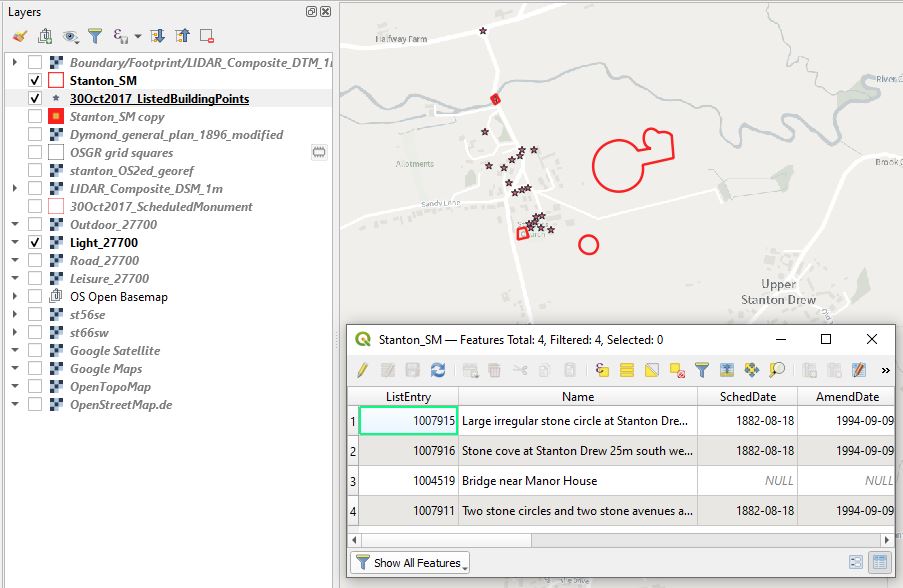

In addition to national and county datasets, many organisations and research groups also curate their own geospatial databases to manage historic environment data, using proprietary or open source platforms. The data are available in a variety of formats from flat-file spreadsheets to GIS ready formats like shapefiles or geopackages.

Being able to extract data from secondary sources and assimilate it into a desk based assessment is a task that relies heavily GIS skills.

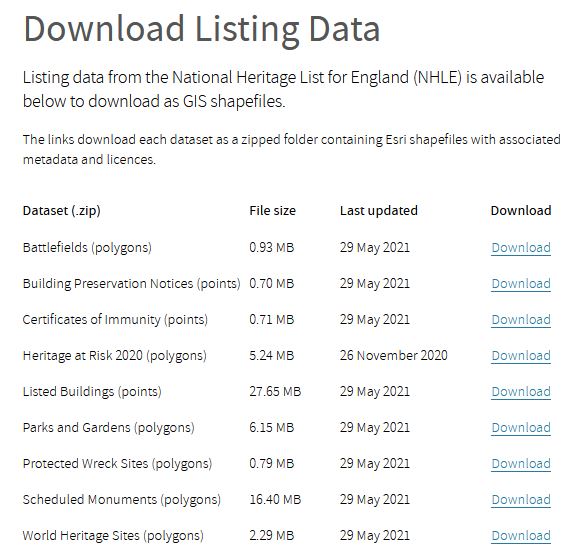

Historic England Data Download

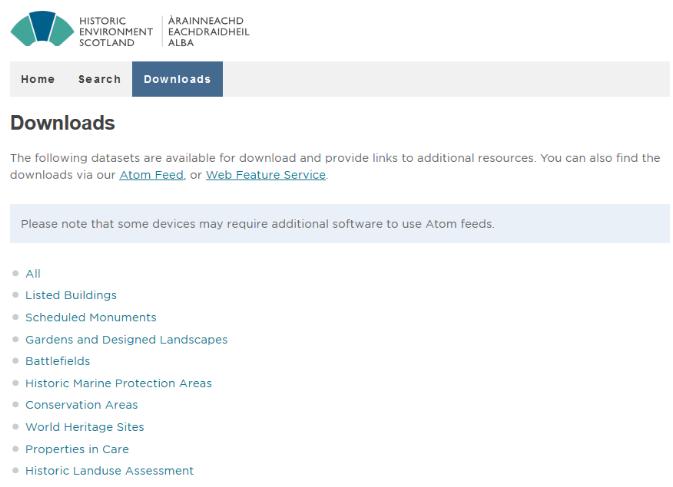

Historic Environment Scotland Canmore Data Download

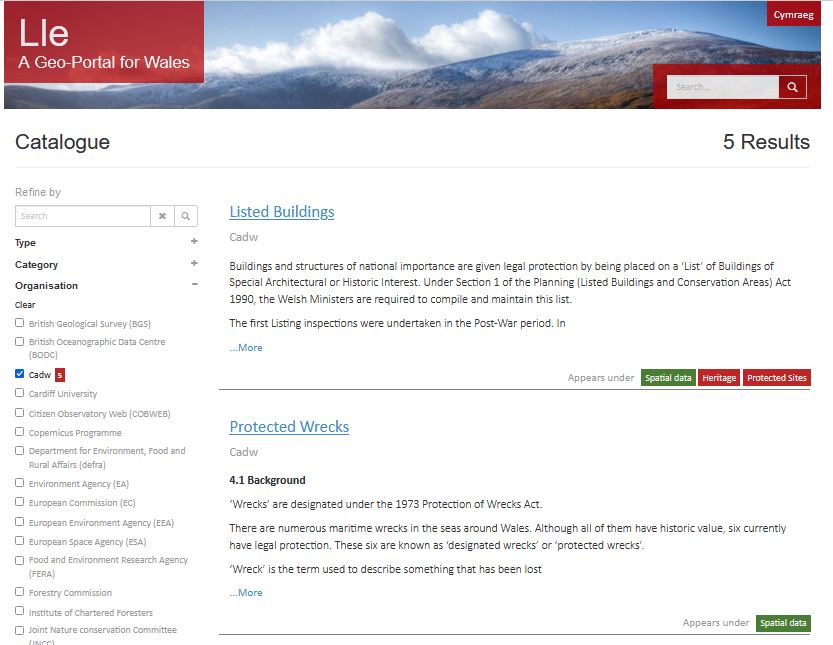

CADW Data Download

Non-Historic Environment Survey Data

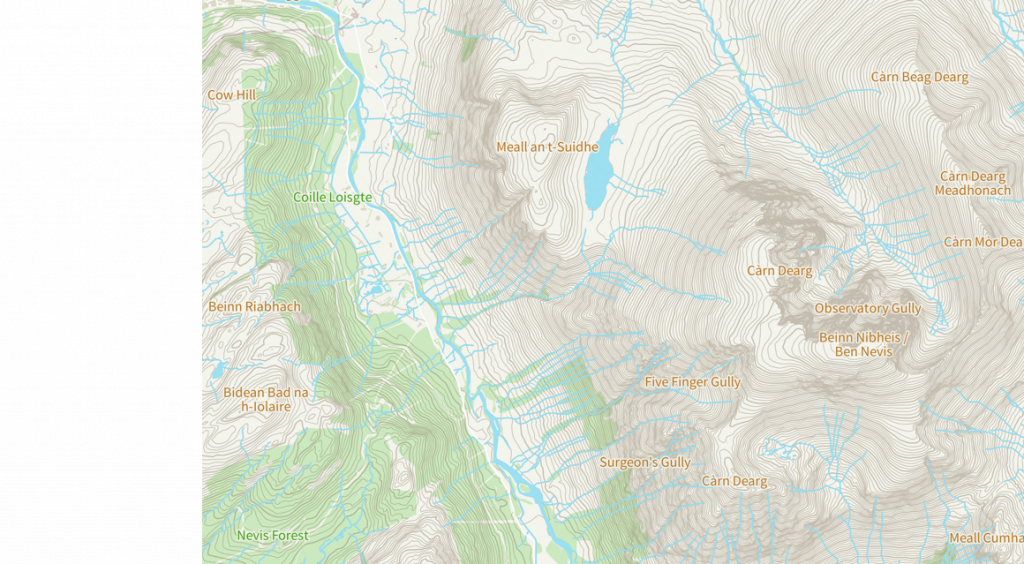

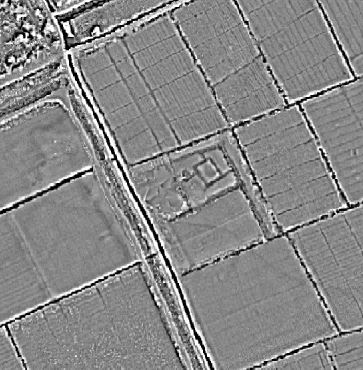

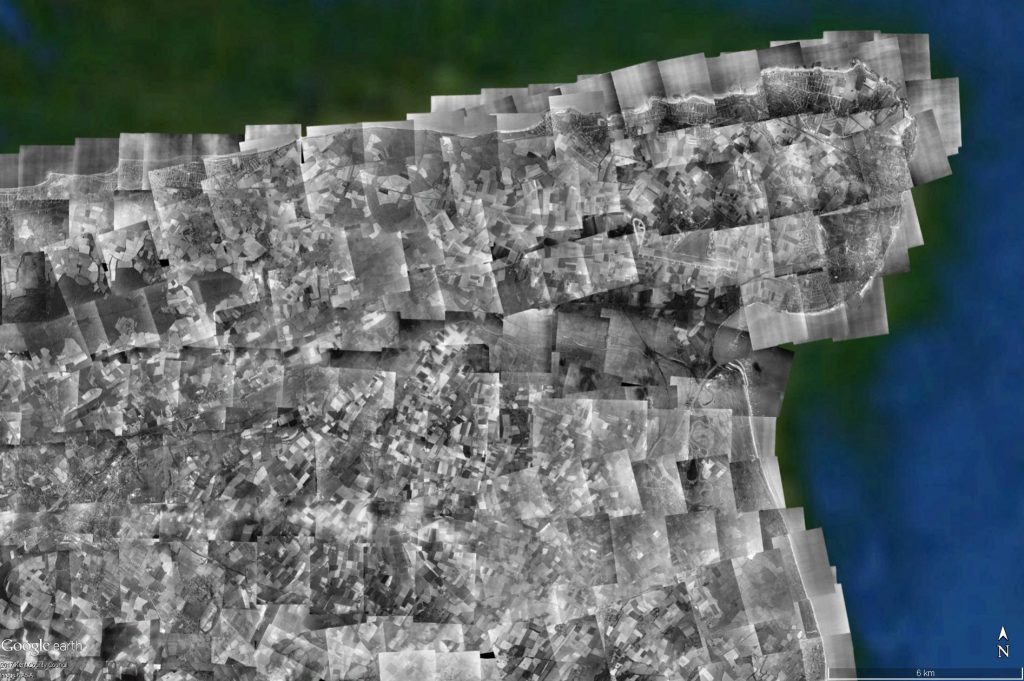

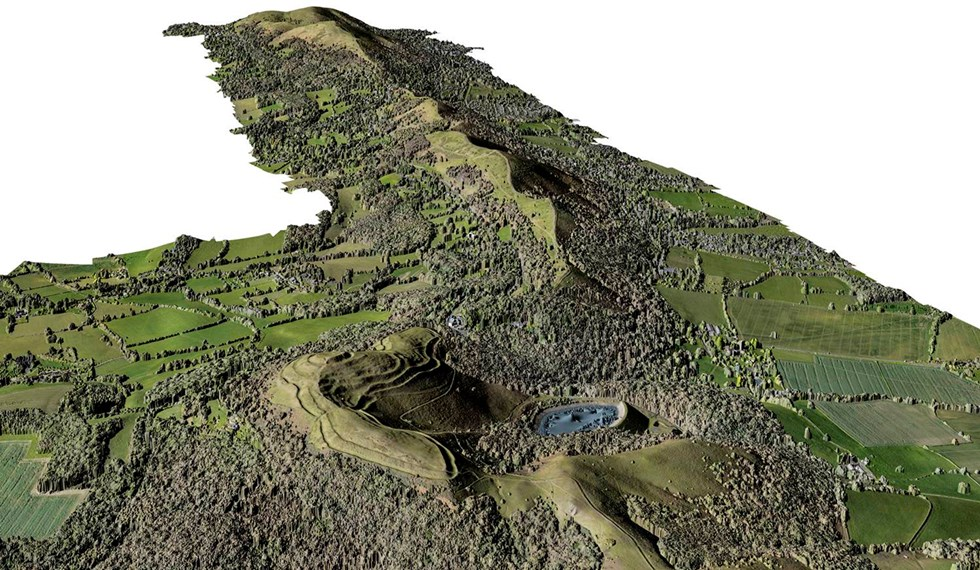

Location data can also be derived from many other types of survey, which are not always collected with the historic environment in mind but nevertheless have huge implications for archaeological reconnaissance and resource management. Examples of these types of data include:

- Satellite imagery

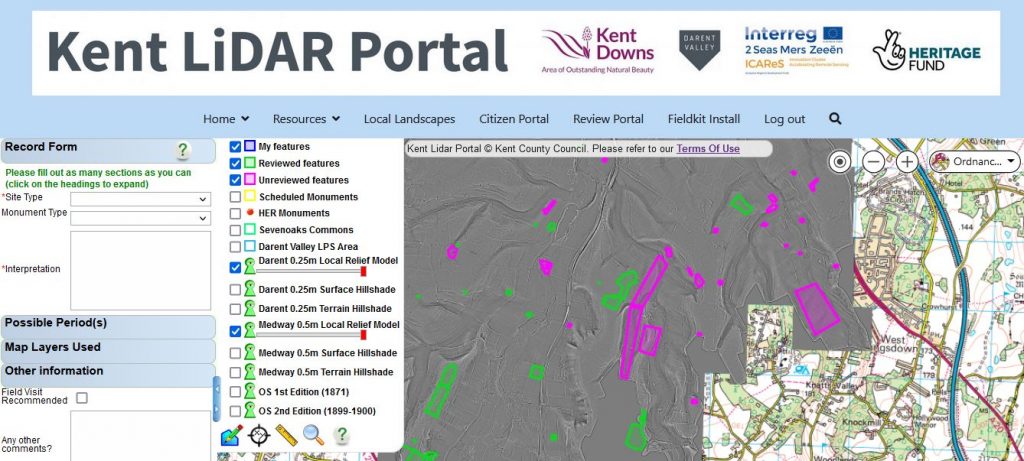

- Lidar data / lidar derived 3D models

- Spectral imagery

- Photogrammetric models

- Sonar and radar survey

- Historic aerial photography

- Historic maps

OS2nd Edition supplied by the National Library of Scotland

Lidar local relief model

Cropmarks at Comberton, Cambridgeshire © Historic England 29365/00

Overlapping vertical aerial photography

Photogrammetric Model © Historic England.

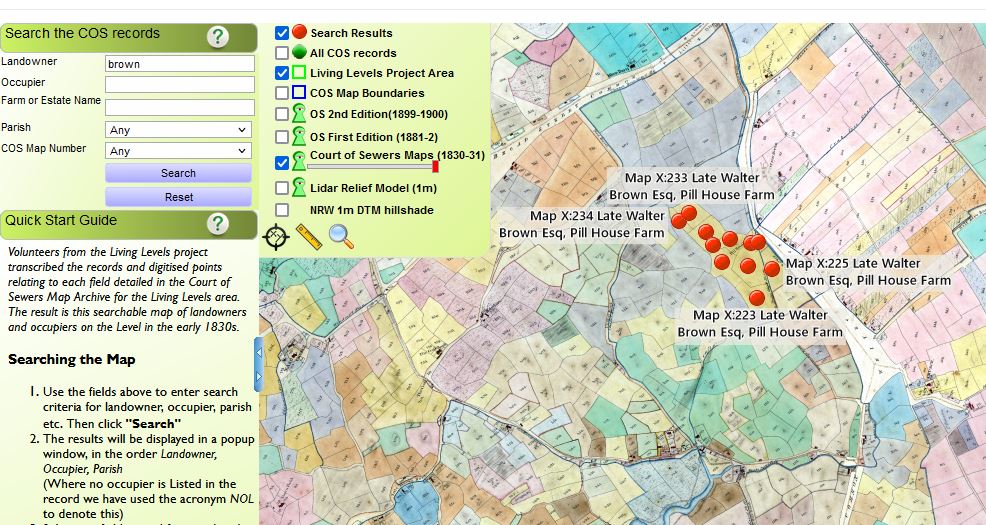

Public Engagement and Dissemination

A key aim of much of the work that we do as historic environment professionals is sharing and collaborating with the wider public to advance understanding of the archaeological resource.

Web maps and map-based data are great tools not only for sharing a project’s results but for facilitating citizen science based collaborative approaches to mapping and understanding the historic environment.

Some consider that this category has significant growth potential over the coming decade as the historic environment sector moves towards greater incorporation of both automated image classification for sources like satellite imagery and lidar data and fully embrace the power of community engagement.

Excellent geospatial data management underpins the quality and success of these projects. Without it we risk creating an unusable “data mountain” and alienating the communities that we wish to serve.

Thinking about data – Questions

Take a few moments to answer the questions below to consolidate what you have learned about different geospatial data types.